Trios of many different genres, styles, movements and themes. I've purposely tried to expand it a bit beyond what I think are the 'best' and more towards personal favourites. They are almost all well-known and should be easy to find. Asterisks will show films that may be more difficult to locate.

Three Great Québecois Films

C.R.A.Z.Y. (Jean-Marc Vallée, 2005) Recommended by me before, a queer coming of age film.

Maelström* (Denis Villeneuve, 2000) A dying fish narrates a strange, emotional tale.

The Decline of the American Empire (Denys Arcand, 1986) Intellectuals talk lots of sex.

Three Great Blaxploitation Films

Bone* (Larry Cohen) Also known as Beverly Hills Nightmare or Housewife, it's deliriously subversive fun.

Cleopatra Jones and the Casino of Gold (Charles Bail, 1975) Campy, ass-kicking Cleo in Macau and Hong Kong.

Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song (Melvin van Peebles, 1971) Revolutionary, landmark blaxploitation.

Three Great Heist Films

The Sting (George Roy Hill, 1973) This Best Picture winner is frothy and fun.

Sexy Beast (Jonathan Glazer, 2001) Gritty British thriller with dynamite performance from Ben Kingsley, who is terrifying as the psychotic Don Logan.

Ocean's Eleven (Steven Soderbergh, 2001) Miles ahead of the original, Soderbergh's film is a stylish delight.

Three Great Cary Grant Screwballs

Arsenic and Old Lace (Frank Capra, 1944) Cary Grant plays the lone sane member of a hilariously murderous family.

His Girl Friday (Howard Hawks, 1940) One of the great scripts of Classic Hollywood, it's the sharpest screwball around.

Bringing Up Baby (Howard Hawks, 1938) Grant shines with Katharine Hepburn, who is delightfully ditzy.

Three Great Anthology Films

Paris, Je T'aime (2006) 20 short films that range from droll character studies to vampire mysteries and beautiful love stories.

Germany in Autumn* (1978) Biting examination of post-War West Germany, featuring shorts from Fassbinder, Kluge and Schlöndorff.

Sin City (Frank Miller, Robert Rodriguez, Quentin Tarantino, 2005) One of the best neo-Noirs.

Three Great Americana Films

The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich, 1971) Stoic view of a small Western town as it transitions to a new era, featuring career-best performances.

Meet Me in St. Louis (Vincent Minnelli, 1944) One of the best American musicals, it's dripping with patriotism and sentimentality... but a closer look reveals much more.

Melvin and Howard* (Jonathan Demme, 1980) An unassuming man's life is changed when he is mysteriously named in the will of none other than Howard Hughes.

Three Great Biopics

Capote (Bennett Miller, 2005) The best biopic ever made, it's subtle, moving and an intense examination into the working process of one of the most controversial and game-changing novels written.

Milk (Gus Van Sant, 2008) Sean Penn walks away with his second Oscar, and Van Sant re-energizes a tired genre with some cinematic flair.

Yankee Doodle Dandy (Michael Curtiz, 1942) Most contemporary audiences know James Cagney for his gangster films -- but he was also a top song and dance man. Here he plays George M. Cohan, "The Man Who Owns Broadway".

Three Great New Hollywood Films Based on a True Story

All the Presidents Men (Alan Pakula, 1976) The breaking of and investigation behind the Watergate Scandal.

Dog Day Afternoon (Sidney Lumet, 1975) A bank robbery goes wrong, and The People eat it up.

Badlands (Terence Malick, 1973) A young couple is on the run and madly in love in this tribute to Americana.

Three Great Shakespeare Films

Titus (Julie Taymor, 1999) Shakespeare's infamous Titus Andronicus goes postmodern.

Macbeth* (Orson Welles, 1948) Welles described his project as "a perfect cross between Wuthering Heights and Bride of Frankenstein", and it's an apt suggestion.

Romeo + Juliet (Baz Lurhmann, 1996) Whirling, kaleidoscopic and pure pop, it's a brave blend that somehow works, and works gloriously.

Three Great Mindbenders

The Trial* (Orson Welles, 1962) Another gem from Orson Welles, featuring spectacular set design.

Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1977) It's hilarious, bizarre and gruesome, and totally worth watching.

Naked Lunch (David Cronenberg, 1991) I still don't know quite what I watched here, but it was sure exhilarating.

Three Great Marriages Falling Apart

Greed (Erich von Stroheim, 1924) This silent epic was shorn by the studio, but in its remains it's still a crowning achievement.

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Mike Nichols, 1966) Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton are at each other's throats with wickedly witty vitriol.

Contempt (Jean-Luc Godard, 1963) Why would your wife suddenly despise everything about you, with only a flimsy excuse? Godard and Bridgette Bardot are a match made in cinematic heaven.

Three Great Documentaries

Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father* (Kurt Kuenne, 2008) Guaranteed to get you sobbing, this is perhaps one of the most emotionally powerful films I've come across.

Grizzly Man (Werner Herzog, 2005) The life and death of bear fanatic Timothy Treadwell.

Night and Fog (Alain Resnais, 1955) One of the first documentaries about the Holocaust, and still among the most poignant and devastating.

Three Great Queer Films

Poison* (Todd Haynes, 1991) Certainly not for all tastes, but those willing to go along with its genre games and whacked-out narratives will have a blast.

The Wedding Banquet (Ang Lee, 1993) Lee went queer long before Brokeback Mountain with this touching and funny adventure of a Taiwanese man pretending to get straight married to hide his gay relationship.

My Beautiful Laundrette (Stephen Frears, 1985) A young Daniel Day Lewis owns the screen.

Three Great French New Wave Films

The Butcher* (Claude Chabrol, 1970) The nouvelle vague goes horror with this chilling character study.

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (Jacques Demy, 1963) And here, it goes American film musical with a jazz operetta that's sure to get you both dancing and crying.

Pierrot le fou (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965) Perhaps Godard's most accessible film, it has all of his experimental and political flourishes but with plenty of laughs, colour and playfulness.

Three Great Gangster Films

White Heat (Raoul Walsh, 1949) James Cagney is electric as a mama's boy turned psychopath.

The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston, 1950) A jewellery caper goes wrong in this classic noir.

Shanghai Triad* (Zhang Yimou, 1995) A provincial boy meets the criminal underworld of 1930s Shanghai in Yimou's Chinese neo-noir.

Monday, July 15, 2013

Quick Reviews

Jurassic Park (2013 Re-Release)

Just as thrilling as I remembered, it's one of Spielberg's adventure masterpieces.

But it being a Spielberg film, you have the precocious child motif: Tim is excellent, while whats-her-face is simply annoying. "I prefer the term hacker!" Sure, you do.

The 3-D, unfortunately, adds nothing to the film as it wasn't designed with it in mind. Instead, we get the downfalls of the process --the film has turned into a muddy, darkened mess-- without any of the supposed bells and whistles.

A+ (C for 3D)

Primal Fear (Gregory Hoblit, 1996)

-Edward Norton is excellent

-score is cliche and invasive in its banality

-a rather unassuming film, not particularly ambitious in straying from formula, but effective as a genre piece.

B

Dangerous Liaisons (Stephen Frears, 1988)

I've seen this on stage, and it's just as crackling on screen. Close is simply on fire, and Malkovich does his best to keep up, and it's an admirable performance. Production design is sumptuous. I do miss the Stratford Festival's touch of an 80s score complete with fired-up, screeching electric guitar, though.

A

Trance (Danny Boyle, 2013)

Stylish, pumping and utterly whacked, the narrative twists and turns over itself in a thrilling if bewildering manner. Strong performances from everyone. But it's all a bit too 'much', isn't it?

B

Das Boot (Wolfgang Petersen, 1981)

That cinematography! Running Steadicam shots through a claustrophobic, tunnel-like U-Boat, swooping through doorways and gliding around people. As a technical achievement, it's superb. As a narrative, it does has its moments that drag, and it's far too long, but somehow it keeps our attention throughout its three-plus hours. [I watched Petersen's directors' cut.] Excellent cast.

A

It Came From Outer Space! (Jack Arnold, 1953)

Utterly wooden dialogue abounds in this Sci-Fi classic. It's a thin analogy that plays much better in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and Ray Bradbury has done much better with more subtle work. Glacial pacing, lots of bland talking, a plot that creeps along like a snail. Skip this one.

D-

The Magnetic Monster (Curt Siodmak, 1953)

I'd never heard of this science fiction piece until I saw it in conjunction with It Came From Outer Space! on TCM. It's a surprisingly witty script, with a good pace and excellent use of stock footage. Game actors play along with the remarkably cerebral going-ons, with B-movie star Richard Carlson doing much better than Outer Space! -- and the scientist in me didn't have to turn off his brain completely. Fun stuff!

A-

Mrs. Miniver (William Wyler, 1943)

Yes, it is sentimental cinema, and unabashedly so. There is the contemporary charge is that it is "propaganda", a term thrown about far too loosely nowadays, but this does not recognize that it was needed and wanted by the public at large and largely void of any insidious motives. Brilliant performances and tight direction as always from Wyler. The flower show is simply one of the most beautiful scenes of Hollywood cinema, with genuine heart-warming pathos.

But there's also a fascinating Oedipus undercurrent between Greer Garson's Mrs. Miniver and her son, played by Richard Ney... who would go on to be Garson's husband just after filming. It strikes me that Garson's Kay Miniver is rather enamoured with her son beyond a simple maternal love: she really does seem to be in love with him. This, of course, could simply be the result of my knowledge that they would be married and my looking for something rather juicy. But it's tempting, no?

A+

Olympus Has Fallen (Antoine Fuqua, 2013)

Gruesome, one of the most violent movies of recent memory. The siege scene is chock-full of death: I shudder to think of just how large the film's body count is. Bystanders get mowed down, a plethora of armed officers are killed, blood flows. Fuqua has terse direction over the carnage, despite a rather poor script. Many "Why?" moments. (Why would you have all three people with the three parts to a super-important code in the same place?) Cheap CGI mars many of the set-pieces, with fake-looking smoke and effects.

C

Just as thrilling as I remembered, it's one of Spielberg's adventure masterpieces.

But it being a Spielberg film, you have the precocious child motif: Tim is excellent, while whats-her-face is simply annoying. "I prefer the term hacker!" Sure, you do.

The 3-D, unfortunately, adds nothing to the film as it wasn't designed with it in mind. Instead, we get the downfalls of the process --the film has turned into a muddy, darkened mess-- without any of the supposed bells and whistles.

A+ (C for 3D)

Primal Fear (Gregory Hoblit, 1996)

-Edward Norton is excellent

-score is cliche and invasive in its banality

-a rather unassuming film, not particularly ambitious in straying from formula, but effective as a genre piece.

B

Dangerous Liaisons (Stephen Frears, 1988)

I've seen this on stage, and it's just as crackling on screen. Close is simply on fire, and Malkovich does his best to keep up, and it's an admirable performance. Production design is sumptuous. I do miss the Stratford Festival's touch of an 80s score complete with fired-up, screeching electric guitar, though.

A

Trance (Danny Boyle, 2013)

Stylish, pumping and utterly whacked, the narrative twists and turns over itself in a thrilling if bewildering manner. Strong performances from everyone. But it's all a bit too 'much', isn't it?

B

Das Boot (Wolfgang Petersen, 1981)

That cinematography! Running Steadicam shots through a claustrophobic, tunnel-like U-Boat, swooping through doorways and gliding around people. As a technical achievement, it's superb. As a narrative, it does has its moments that drag, and it's far too long, but somehow it keeps our attention throughout its three-plus hours. [I watched Petersen's directors' cut.] Excellent cast.

A

It Came From Outer Space! (Jack Arnold, 1953)

Utterly wooden dialogue abounds in this Sci-Fi classic. It's a thin analogy that plays much better in Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and Ray Bradbury has done much better with more subtle work. Glacial pacing, lots of bland talking, a plot that creeps along like a snail. Skip this one.

D-

The Magnetic Monster (Curt Siodmak, 1953)

I'd never heard of this science fiction piece until I saw it in conjunction with It Came From Outer Space! on TCM. It's a surprisingly witty script, with a good pace and excellent use of stock footage. Game actors play along with the remarkably cerebral going-ons, with B-movie star Richard Carlson doing much better than Outer Space! -- and the scientist in me didn't have to turn off his brain completely. Fun stuff!

A-

Mrs. Miniver (William Wyler, 1943)

Yes, it is sentimental cinema, and unabashedly so. There is the contemporary charge is that it is "propaganda", a term thrown about far too loosely nowadays, but this does not recognize that it was needed and wanted by the public at large and largely void of any insidious motives. Brilliant performances and tight direction as always from Wyler. The flower show is simply one of the most beautiful scenes of Hollywood cinema, with genuine heart-warming pathos.

But there's also a fascinating Oedipus undercurrent between Greer Garson's Mrs. Miniver and her son, played by Richard Ney... who would go on to be Garson's husband just after filming. It strikes me that Garson's Kay Miniver is rather enamoured with her son beyond a simple maternal love: she really does seem to be in love with him. This, of course, could simply be the result of my knowledge that they would be married and my looking for something rather juicy. But it's tempting, no?

A+

Olympus Has Fallen (Antoine Fuqua, 2013)

Gruesome, one of the most violent movies of recent memory. The siege scene is chock-full of death: I shudder to think of just how large the film's body count is. Bystanders get mowed down, a plethora of armed officers are killed, blood flows. Fuqua has terse direction over the carnage, despite a rather poor script. Many "Why?" moments. (Why would you have all three people with the three parts to a super-important code in the same place?) Cheap CGI mars many of the set-pieces, with fake-looking smoke and effects.

C

Sunday, April 7, 2013

"Cimarron" and "Driving Miss Daisy"

Oh, Cimarron. I've finally caught up with this 1931 Best Picture winner, and its (rather lowly) reputation --a spectacular opening sequence followed by a plethora of stereotypes that make modern audiences squirm uncomfortably-- isn't unwarranted.

Progressively Backwards

The film tracks the course of forty years --from 1890 to present day 1940-- as we see the Oklahoma settlement Osage (the name of a Siouan tribe) evolve from a midwest boomtown of an instantaneous 10,000 to a modern urban city, focusing on the lives of Yancey Cravat and his wife Sabra. Yancey is a strapping fella with big ambitions and a big heart; Sabra comes from a wealthy, well-to-do family who disowns her when she decides to follow Yancey as he ventures into the West to start a newspaper. Some have described Cimarron as a Western, which describes the first half or so of the movie quite well, and as a Western, thematically the film is about progress, civilization... and the White Man's burden to enlighten lesser peoples. Cimarron is incredibly --and dare I say it?-- hilariously racist, sexist and every other -ist you can think of, as it tries so hard to be "progressive".

Yes, that's right. It seems the Big Theme of Cimarron is that it takes a few Great White Men to lead a country, and that this can be a heavy burden, especially for those that love them. Yancey fights for what is 'right', cleaning the town of criminals, but also protecting those that are misunderstood by dominant society. As such, he treats his black servant boy with kindness, defends the town's Madam from old-fashioned ninnies who want her in jail, and particularly, patting the heads of the local Indians. Cimarron, you see, is a big pile of condescending hooey.

And the reason why it's so eye-rolling and guffaw-worthy is that the film still tries to have it both ways: as much as it says that 'we' must be nice to the lowly poor demographics, it wants to get a laugh out of them too.

Here's how a typical example plays out in the film:

Yancy and Sabra's young son Cimarron is playing out in the yard when a Tall Silent Indian approaches him. The young boy looks up, says hello, and is given a small gift from the nice man. Into the house he runs, presenting his prize to his mother... who then scolds him, shrilly yelling: "How many times have I told you not to talk to those dirty, filthy Indians?" Now at this point, it's hard to tell what the film is doing: is this supposed to be funny? Is this supposed to be an ignorant statement that we, in our enlightened 1940 selves, are supposed to gasp at? Or are the filmmakers expecting a great deal of the audience to agree with Sabra? I suspect that it might be the final, because we cut to Yancey discussing politics where he declares "the Cherokee are too smart to donate money to a race that robbed them of their Birthright."

That's right, audience! The Cherokee aren't villains or savages, but were robbed of their Birthright, so that's why they're sometimes aggressive or whatever. They're actually a noble race. All of them.

But the film seems to have something to say about nearly every archetype and demographic.

The Wacky Denizens of Osage

Ricky, the caricature of the stuttering town idiot who is mocked by everyone, including Yancey -- who also gives him a job as printer. See? Stuttering people can be useful! And they're pretty gosh-darned hilarious, too.

Mr. Levy, the Effeminate Urbanite Jew and merchant. The Black Hats at one point mock him as he rolls his cart full of womenswear down the street, eventually beating him and forcing him to drink some booze. He is saved by Yancey, and becomes a close friend of Sabra -- but never more than a friend, even though Yancey disappears for years (maybe even a decade) at a time and Levy is obviously enamoured with Sabra.

Isaiah the "coloured boy" help. Ohhhhhh boy. It's everything that you could think of. At one point, the entire town laughs at him because of his attempt to look "all Sunday like". A cartful of watermelon is pointed out to him as an irresistible treat. He's more comic relief, y'all. Oh, and gets killed while trying to save the white children from outlaws. How noble!

The schoolteacher "intellectual" Old Maid, with faux-soprano voice while speaking and melismatic alto when she sings. She's the local Temperance leader (of course) and is rather vocal about the shenanigans of...

Miss Dixie Lee, the local Madame, Independent Woman and "a viper lurking in our midst!" She is, ultimately, the classic Whore with a Heart of Gold whom Yancey the lawyer defends from being run out of town. Obviously Sabra hates her. A lot.

Ruby, the Indian Princess and Sabra's hired help when Yancey goes off on an adventure for years. She's also Cimarron's love interest, which is another attempt at showing just how progressive the film is. Naturally, Sabra doesn't approve of her white son mixing with an Indian and making half-breeds, but she turns around by the end of the film to respect her daughter-in-law. See below.

Forward! To Destiny!

By 1907, Donna becomes a horrid little gold digger and "Cim" wants to marry Ruby. And what, pray, does Sabra think? Exactly what you'd expect.

But as we move forward in time, we get well-placed lines and images that help us feel oh-so-modern. Someone declares "Cuba will never be able to govern itself!". An advertisement shows us the "Latest Styles at Levy's". See see the first car in 1907, the temperance movement in full spring. Yancey Cravat runs for Governor, representing --what else?-- the Progressive Party. He's running on extending citizenship to "the red man", which Sabra vehemently opposes. Time further passes, Ricky's stutter gets better (hahahahahaha!), and in the final scene at the Savoy-Bixby hotel Sabra, whom has been elected member of congress, makes a big speech about progress and how wonderful her husband is. And where, pray, is her husband? Why, disappeared for years. We assume he lost the election way back when, but it's not explicitly said other than that he runs off due to "wanderlust". (And we're supposed to like this guy?) But Ruby is accepted as part of the family! Yay! And she 'extends wishes using the words taught her as a child'... insert a cringe-worthy "Indian" greeting that's all so noble and crap. And Sabra introduces her to a crowd of people as her daughter-in-law! See? A change of heart. You can change, too!

The film ends with a reuniting of Sabra and Yancey, a little bit of tragedy, and the erection of a big statue. Hooray!

Driving Miss Daisy (Bruce Beresford, 1990)

A strangely fitting pair with Cimarron, Beresford's film is a loving tribute to Stockholm Syndrome in the American South. The film is a laughless comedy, instead being a gentle, sentimental character drama with some rather problematic ideology. It's another pat-yourself-on-the-back example of glib liberalism, the lesson seems to be that there are good whites, and the blacks that happen to work for them should be glad that they do. Huh?

Yessum, that's what it sure seems like. Hoke is everything you could want in a servant: lively, funny, dedicated. He'll do anything for Miss Daisy, and it's shown quite why other than he's a magical negro with a funny laugh. See? White people, especially when they're Jewish and, y'know, understand, can be benevolent and teach you to read and give you pie.

Frankly, I don't have too much else to say about Driving Miss Daisy. It somehow won Best Picture, with the big story being that Spike Lee's fiery Do the Right Thing wasn't even nominated, and a far better picture of American racism. Lee would go on to do some of his own problematic films (Bamboozled, I'm looking at you) but that the Academy went over DtRT for this is just embarrassing. Jessica Tandy's win for leading actress, on the other hand, isn't entirely wrong. It's a powerful performance, and easily the best thing about the film.

Oh, and the score? Ugh. Hans Zimmer and his keyboards doing daytime-TV riffs. Probably the best example of why I'm not the biggest Zimmer fan.

Progressively Backwards

The film tracks the course of forty years --from 1890 to present day 1940-- as we see the Oklahoma settlement Osage (the name of a Siouan tribe) evolve from a midwest boomtown of an instantaneous 10,000 to a modern urban city, focusing on the lives of Yancey Cravat and his wife Sabra. Yancey is a strapping fella with big ambitions and a big heart; Sabra comes from a wealthy, well-to-do family who disowns her when she decides to follow Yancey as he ventures into the West to start a newspaper. Some have described Cimarron as a Western, which describes the first half or so of the movie quite well, and as a Western, thematically the film is about progress, civilization... and the White Man's burden to enlighten lesser peoples. Cimarron is incredibly --and dare I say it?-- hilariously racist, sexist and every other -ist you can think of, as it tries so hard to be "progressive".

Yes, that's right. It seems the Big Theme of Cimarron is that it takes a few Great White Men to lead a country, and that this can be a heavy burden, especially for those that love them. Yancey fights for what is 'right', cleaning the town of criminals, but also protecting those that are misunderstood by dominant society. As such, he treats his black servant boy with kindness, defends the town's Madam from old-fashioned ninnies who want her in jail, and particularly, patting the heads of the local Indians. Cimarron, you see, is a big pile of condescending hooey.

And the reason why it's so eye-rolling and guffaw-worthy is that the film still tries to have it both ways: as much as it says that 'we' must be nice to the lowly poor demographics, it wants to get a laugh out of them too.

Here's how a typical example plays out in the film:

Yancy and Sabra's young son Cimarron is playing out in the yard when a Tall Silent Indian approaches him. The young boy looks up, says hello, and is given a small gift from the nice man. Into the house he runs, presenting his prize to his mother... who then scolds him, shrilly yelling: "How many times have I told you not to talk to those dirty, filthy Indians?" Now at this point, it's hard to tell what the film is doing: is this supposed to be funny? Is this supposed to be an ignorant statement that we, in our enlightened 1940 selves, are supposed to gasp at? Or are the filmmakers expecting a great deal of the audience to agree with Sabra? I suspect that it might be the final, because we cut to Yancey discussing politics where he declares "the Cherokee are too smart to donate money to a race that robbed them of their Birthright."

That's right, audience! The Cherokee aren't villains or savages, but were robbed of their Birthright, so that's why they're sometimes aggressive or whatever. They're actually a noble race. All of them.

But the film seems to have something to say about nearly every archetype and demographic.

The Wacky Denizens of Osage

Ricky, the caricature of the stuttering town idiot who is mocked by everyone, including Yancey -- who also gives him a job as printer. See? Stuttering people can be useful! And they're pretty gosh-darned hilarious, too.

Mr. Levy, the Effeminate Urbanite Jew and merchant. The Black Hats at one point mock him as he rolls his cart full of womenswear down the street, eventually beating him and forcing him to drink some booze. He is saved by Yancey, and becomes a close friend of Sabra -- but never more than a friend, even though Yancey disappears for years (maybe even a decade) at a time and Levy is obviously enamoured with Sabra.

Isaiah the "coloured boy" help. Ohhhhhh boy. It's everything that you could think of. At one point, the entire town laughs at him because of his attempt to look "all Sunday like". A cartful of watermelon is pointed out to him as an irresistible treat. He's more comic relief, y'all. Oh, and gets killed while trying to save the white children from outlaws. How noble!

The schoolteacher "intellectual" Old Maid, with faux-soprano voice while speaking and melismatic alto when she sings. She's the local Temperance leader (of course) and is rather vocal about the shenanigans of...

Miss Dixie Lee, the local Madame, Independent Woman and "a viper lurking in our midst!" She is, ultimately, the classic Whore with a Heart of Gold whom Yancey the lawyer defends from being run out of town. Obviously Sabra hates her. A lot.

Ruby, the Indian Princess and Sabra's hired help when Yancey goes off on an adventure for years. She's also Cimarron's love interest, which is another attempt at showing just how progressive the film is. Naturally, Sabra doesn't approve of her white son mixing with an Indian and making half-breeds, but she turns around by the end of the film to respect her daughter-in-law. See below.

Forward! To Destiny!

By 1907, Donna becomes a horrid little gold digger and "Cim" wants to marry Ruby. And what, pray, does Sabra think? Exactly what you'd expect.

But as we move forward in time, we get well-placed lines and images that help us feel oh-so-modern. Someone declares "Cuba will never be able to govern itself!". An advertisement shows us the "Latest Styles at Levy's". See see the first car in 1907, the temperance movement in full spring. Yancey Cravat runs for Governor, representing --what else?-- the Progressive Party. He's running on extending citizenship to "the red man", which Sabra vehemently opposes. Time further passes, Ricky's stutter gets better (hahahahahaha!), and in the final scene at the Savoy-Bixby hotel Sabra, whom has been elected member of congress, makes a big speech about progress and how wonderful her husband is. And where, pray, is her husband? Why, disappeared for years. We assume he lost the election way back when, but it's not explicitly said other than that he runs off due to "wanderlust". (And we're supposed to like this guy?) But Ruby is accepted as part of the family! Yay! And she 'extends wishes using the words taught her as a child'... insert a cringe-worthy "Indian" greeting that's all so noble and crap. And Sabra introduces her to a crowd of people as her daughter-in-law! See? A change of heart. You can change, too!

The film ends with a reuniting of Sabra and Yancey, a little bit of tragedy, and the erection of a big statue. Hooray!

Driving Miss Daisy (Bruce Beresford, 1990)

A strangely fitting pair with Cimarron, Beresford's film is a loving tribute to Stockholm Syndrome in the American South. The film is a laughless comedy, instead being a gentle, sentimental character drama with some rather problematic ideology. It's another pat-yourself-on-the-back example of glib liberalism, the lesson seems to be that there are good whites, and the blacks that happen to work for them should be glad that they do. Huh?

Yessum, that's what it sure seems like. Hoke is everything you could want in a servant: lively, funny, dedicated. He'll do anything for Miss Daisy, and it's shown quite why other than he's a magical negro with a funny laugh. See? White people, especially when they're Jewish and, y'know, understand, can be benevolent and teach you to read and give you pie.

Frankly, I don't have too much else to say about Driving Miss Daisy. It somehow won Best Picture, with the big story being that Spike Lee's fiery Do the Right Thing wasn't even nominated, and a far better picture of American racism. Lee would go on to do some of his own problematic films (Bamboozled, I'm looking at you) but that the Academy went over DtRT for this is just embarrassing. Jessica Tandy's win for leading actress, on the other hand, isn't entirely wrong. It's a powerful performance, and easily the best thing about the film.

Oh, and the score? Ugh. Hans Zimmer and his keyboards doing daytime-TV riffs. Probably the best example of why I'm not the biggest Zimmer fan.

Saturday, March 30, 2013

Short Reviews

From Dusk til Dawn (Rodriguez, 1996)

It's like two grindhouse movies stuck awkwardly together, with a sudden shift in tone and authorial vision. The first half if like hyperbolic Tarantino, with some of his most risqué and blatantly tasteless plot twists. The second half is Rodriguez going super cheesy and over-the-top with his porno horror comedy. Horror comedies never really work out, and this is no exception to that general rule. Yet there are some clever sight gags: a cross made out of a shotgun, a collection of trucker bric-a-brac, holy water filled condoms and water guns, a disco ball turned into a rotating gun of sunlight. A strange sentimentality and attempts at emotion that pervade the second half of the film strike as a little too much, and out of place amongst the mayhem -- and perhaps this entire stew is purposely incongruent.

Like most of Tarantino's scripts, there is a pervading element of morality, as characters grapple with conventional ethics. A rape motif runs through, with Tarantino himself as a crazed, raping, murdering and 'a little bit slow' psychopath -- and is unsurprisingly the most memorable character of the bunch. He doesn't understand basic ethics, and has a child-like behaviour mixed with brutal sadism, like an id gone wild. But is it the most powerful evidence I've seen yet of Tarantino's ideological problems? Oh yes.

B-

CSA: Confederate States of America (Willmott, 2004)

-as subtle as producer Spike Lee's Bamboozled, but thankfully without the awful melodrama.

-too much emphasis on race, and a belief that it is not the insidious and sly racism but the over-the-top minstrelsy that dominates American race relations

-full of questionable historical revisionism: Canada as Russia? Slavery really still exists?

-acting in commercials, recreations and meta-media is too hokey and corny, far beyond tongue-in-cheek into the eye-rolling.

-cheap jokes are the most effective

C

Galaxy Quest (Parisot, 1999)

-goofy, silly, obviously clever but still a delight. It doesn't bite too deep or too harshly, so that genuine fans of science fiction and acting has-beens will laugh at themselves rather than feel offended. It's gentle jabbing instead of mocking, and more of a celebration of Trekkie geekery than a tear-down.

-inventive visuals

-quick and clean narrative, a game cast (although more to be desired with the female roles, the only two worth mentioning inevitably love interests).

B

Winter's Bone (Granik, 2010)

Chilly drama

-Jennifer Lawrence's star-making performance is lived in, with nary a false note

-some could accuse the film of painting a portrait of the coal belt as a backwards cesspool, but instead the film is really showing the underbelly of any society: we do see so-called 'normal folk' doing normal things, like going to school or running a farm that is more than just scraping by.

-haunting moments, like in the climatic boat scene

-beautiful cinematography

A

Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (Ritchie, 1998)

Tarantino-lite, with far too many self-consiously clever twists and turns. The plot is near impossible to follow, and I had no real desire to actually figure it all out, unlike the best of the subgenre. It's not thrilling, it's exhausting. Best moments are in the English goofiness and violent slang.

C

The Young Victoria (Vallee, 2009)

I'm a sucker for handsome costume dramas, and this one didn't let me down. Yes, the narrative is a bit too condensed, and ends awkwardly, but the production design is absolutely stunning and the acting top-notch. Jean-Marc Vallee directs with flair.

B+

Valhalla Rising ()

Molasses-slow and groggingly "heavy", elliptical to a fault. As a mood piece it's near parodic, but when it works, it is intense: a drug trip with droning guitars is simply stunning.

C-

Bernie ()

Rather delightful comedy with a fantastic leading performance by Jack Black. Just the right amount of whimsy, kitsch and dark humour, with a mockumentary twist that actually works quite well. Unsurprisingly, some of the real townsfolk were involved in the making of the film and even show up as interviewees.

B+

It's like two grindhouse movies stuck awkwardly together, with a sudden shift in tone and authorial vision. The first half if like hyperbolic Tarantino, with some of his most risqué and blatantly tasteless plot twists. The second half is Rodriguez going super cheesy and over-the-top with his porno horror comedy. Horror comedies never really work out, and this is no exception to that general rule. Yet there are some clever sight gags: a cross made out of a shotgun, a collection of trucker bric-a-brac, holy water filled condoms and water guns, a disco ball turned into a rotating gun of sunlight. A strange sentimentality and attempts at emotion that pervade the second half of the film strike as a little too much, and out of place amongst the mayhem -- and perhaps this entire stew is purposely incongruent.

Like most of Tarantino's scripts, there is a pervading element of morality, as characters grapple with conventional ethics. A rape motif runs through, with Tarantino himself as a crazed, raping, murdering and 'a little bit slow' psychopath -- and is unsurprisingly the most memorable character of the bunch. He doesn't understand basic ethics, and has a child-like behaviour mixed with brutal sadism, like an id gone wild. But is it the most powerful evidence I've seen yet of Tarantino's ideological problems? Oh yes.

B-

CSA: Confederate States of America (Willmott, 2004)

-as subtle as producer Spike Lee's Bamboozled, but thankfully without the awful melodrama.

-too much emphasis on race, and a belief that it is not the insidious and sly racism but the over-the-top minstrelsy that dominates American race relations

-full of questionable historical revisionism: Canada as Russia? Slavery really still exists?

-acting in commercials, recreations and meta-media is too hokey and corny, far beyond tongue-in-cheek into the eye-rolling.

-cheap jokes are the most effective

C

Galaxy Quest (Parisot, 1999)

-goofy, silly, obviously clever but still a delight. It doesn't bite too deep or too harshly, so that genuine fans of science fiction and acting has-beens will laugh at themselves rather than feel offended. It's gentle jabbing instead of mocking, and more of a celebration of Trekkie geekery than a tear-down.

-inventive visuals

-quick and clean narrative, a game cast (although more to be desired with the female roles, the only two worth mentioning inevitably love interests).

B

Winter's Bone (Granik, 2010)

Chilly drama

-Jennifer Lawrence's star-making performance is lived in, with nary a false note

-some could accuse the film of painting a portrait of the coal belt as a backwards cesspool, but instead the film is really showing the underbelly of any society: we do see so-called 'normal folk' doing normal things, like going to school or running a farm that is more than just scraping by.

-haunting moments, like in the climatic boat scene

-beautiful cinematography

A

Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (Ritchie, 1998)

Tarantino-lite, with far too many self-consiously clever twists and turns. The plot is near impossible to follow, and I had no real desire to actually figure it all out, unlike the best of the subgenre. It's not thrilling, it's exhausting. Best moments are in the English goofiness and violent slang.

C

The Young Victoria (Vallee, 2009)

I'm a sucker for handsome costume dramas, and this one didn't let me down. Yes, the narrative is a bit too condensed, and ends awkwardly, but the production design is absolutely stunning and the acting top-notch. Jean-Marc Vallee directs with flair.

B+

Valhalla Rising ()

Molasses-slow and groggingly "heavy", elliptical to a fault. As a mood piece it's near parodic, but when it works, it is intense: a drug trip with droning guitars is simply stunning.

C-

Bernie ()

Rather delightful comedy with a fantastic leading performance by Jack Black. Just the right amount of whimsy, kitsch and dark humour, with a mockumentary twist that actually works quite well. Unsurprisingly, some of the real townsfolk were involved in the making of the film and even show up as interviewees.

B+

Monday, March 25, 2013

"Recommend me some movies!" #2: A little bit arty

You've seen a lot of the Hollywood stuff, and you want to go a little deeper down the cinema rabbit hole... but not too much. This set of films tries to avoid the "that's a bit too weird" and the "I didn't get that at all" potentialities (well, mostly), but wants you to expand your repertoire beyond contemporary and recent mainstream cinema. Many of these films would fit well into an Introduction to Film Studies course, and I've even taken inspiration from courses I've taken or even helped teach. What would you recommend?

European Art Cinema

Post-WWII, often attempting a more radical approach to narrative, featuring the use of psychology and intense characterizations over plot. The question is not "What's going to happen next?", but instead "Why is this happening?". Various "new wave" movements sprung up during the 1960s, lead by young filmmakers who reacted against what Cahiers du cinéma called "daddy's cinema".

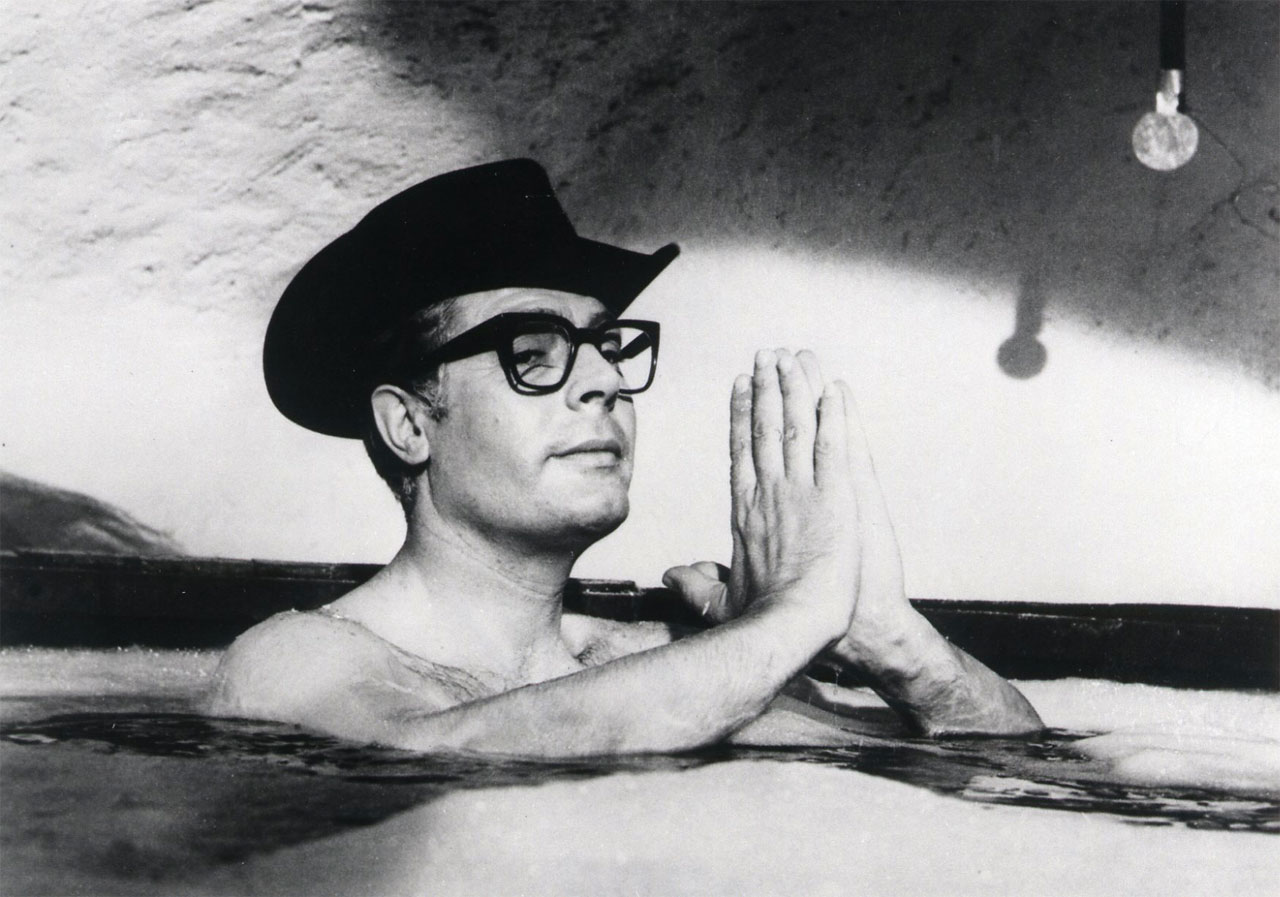

8 1/2 (Federico Fellini, 1963, Italy)

One of the towering achievements of cinematic history, Fellini's elliptical, wandering, ambitious and surreal film is an art house epic. Hugely influential, this film is among the most difficult on this list for some audiences, while others will eat this epic up.

The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman, 1957, Sweden)

A good introduction to the stoic cinema of Sweden's premier auteur, Ingmar Bergman. A medieval knight goes on his business while being stalked by Death himself as they play a game of chess.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (Rainier Werner Fassbinder, 1974, West Germany)

Fassbinder was one of the most prolific directors out there, but this surely ranks as his most heart-wrenching yet accessible of his work. Excellent performances dominate.

Shoot the Piano Player (François Truffaut, 1960, France)

Truffaut's thriller-comedy-tragedy of a second feature film is far more playful than his seminal debut The 400 Blows (1959), but still features many of the same qualities that made the French New Wave so integral to film history.

Band of Outsiders (Jean-Luc Godard, 1964, France)

Like Shoot the Piano Player, this is Godard at his most playful and loose. Anna Karina, Godard's future wife, is simply delightful in every film she appears in, but rarely moreso than here. Look for an impromptu dance sequence that surely ranks as one of the most marvellous sequences in cinema.

American New Wave/The New Hollywood

Young filmmakers react to Classical Hollywood and the collapse of the Production Code that forbade many 'controversial' topics and their depiction.

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

Silent Cinema

While there are many places to begin with an incredible wealth of material, it seems that many audiences either don't know where to begin or are hesitant to start, afraid that they will be bored.

Nosferatu (FW Murnau, 1922, Germany)

This unauthorized version of Dracula was almost completely destroyed by Bram Stoker's widow. Thankfully, she didn't succeed, and we now have the ability to see one of the most entertaining and effective of all silent films. Max Schreck's remarkable performance as the vampire has become the stuff of legend, with fanciful suggestions that he was indeed a vampire himself (the basis of the 2000 film Shadow of the Vampire): how else can you explain those hypnotic, unearthly movements, and that incredible stare and makeup?

Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927, Germany)

More hypnotic movements in this German Expressionist masterpiece and one of the most influential science fiction pieces. The narrative is near-mythic in its battle of good and evil, but it's the massive visuals and the towering art direction that make this a must-see for anyone who considers themselves a lover of cinema.

The Red Spectre (Sigundo de Chomón and Ferdinand Zecca, 1907, Spain)

This is one of my professor Tobias and mine favourite films, and a perfect example of what Tom Gunning calls the Cinema of Attraction. A devil-like figure performs tricks and magic.

Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalì, 1929, France/Spain)

No art house list would be complete without Un Chien Andalou. Just watch it, and don't read anything about it before you do. You'll, uh, thank me.

Three East Asian Films

Late Spring (Yasujiro Ozu, 1949, Japan)

Ozu's meditative style is often called the 'most Japanese' of his peers, with a purposeful but slow pace and muted yet strong emotions. Late Spring may be considered by many as lesser than his masterpiece Tokyo Story, but I find the film to be one of the emotionally powerful films ever made. A widowed father watches as his only daughter goes through the milestone of marriage.

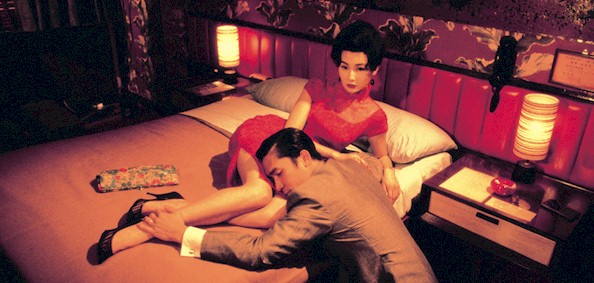

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar Wai, 2000, Hong Kong)

Contemporary Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar Wai made quite a splash with this film just over a decade ago. It's oozing with passion from every shot, and the romance is humid yet never quite consummated. A beautiful film.

Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950)

One of my personal favourites, Rashomon is Kurosawa at his most focused and inventive. Multiple people have witnessed a murder, but each have different stories to tell of exactly what happened. Who is telling the truth? Is there any way that we can determine this?

European Art Cinema

Post-WWII, often attempting a more radical approach to narrative, featuring the use of psychology and intense characterizations over plot. The question is not "What's going to happen next?", but instead "Why is this happening?". Various "new wave" movements sprung up during the 1960s, lead by young filmmakers who reacted against what Cahiers du cinéma called "daddy's cinema".

8 1/2 (Federico Fellini, 1963, Italy)

One of the towering achievements of cinematic history, Fellini's elliptical, wandering, ambitious and surreal film is an art house epic. Hugely influential, this film is among the most difficult on this list for some audiences, while others will eat this epic up.

The Seventh Seal (Ingmar Bergman, 1957, Sweden)

A good introduction to the stoic cinema of Sweden's premier auteur, Ingmar Bergman. A medieval knight goes on his business while being stalked by Death himself as they play a game of chess.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (Rainier Werner Fassbinder, 1974, West Germany)

Fassbinder was one of the most prolific directors out there, but this surely ranks as his most heart-wrenching yet accessible of his work. Excellent performances dominate.

Shoot the Piano Player (François Truffaut, 1960, France)

Truffaut's thriller-comedy-tragedy of a second feature film is far more playful than his seminal debut The 400 Blows (1959), but still features many of the same qualities that made the French New Wave so integral to film history.

Band of Outsiders (Jean-Luc Godard, 1964, France)

Like Shoot the Piano Player, this is Godard at his most playful and loose. Anna Karina, Godard's future wife, is simply delightful in every film she appears in, but rarely moreso than here. Look for an impromptu dance sequence that surely ranks as one of the most marvellous sequences in cinema.

American New Wave/The New Hollywood

Young filmmakers react to Classical Hollywood and the collapse of the Production Code that forbade many 'controversial' topics and their depiction.

Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)

Robert DeNiro's iconic performance as Travis Bickle is only one part of Scorsese's haunting masterpiece. It's dark, gritty, melancholic and profoundly disturbing -- and yet somehow supremely entertaining.

Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1986)

Although too late to be considered a true member of the New Hollywood, Blue Velvet remains one of the most integral of American films. Similar to Taxi Driver in that it's the disturbing portrait of the evil that lurks under the veneer of the American Dream, Lynch's masterpiece is a surreal mystery film with some of the greatest performances out there. Dennis Hopper truly disturbs as the unknown-gas-sniffing, sexual deviant and psychotic Frank Booth: one of cinema's greatest villains.

M*A*S*H (Robert Altman, 1970)

A little bit different than the spin-off television series, Altman's film is more biting, satirical and even a little bit bawdy -- but always worth a good belly laugh.

Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1977)

This Best Picture winner is sometimes maligned by fanboys as the film that beat Star Wars for the Oscar, but it's difficult to argue after having seen it. Hilarious from start to finish, with some miraculous filmmaking skill and wonderful non-sequiters. Diane Keaton justly won the Academy Award for her iconic performance as the titular Annie Hall.

The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich, 1971)

This stark coming-of-age tale was one of the major breakthroughs of the New Hollywood. A melancholic and moving view of a small mid-west town, with strong performances and homages to Classical Hollywood cinema.

Although too late to be considered a true member of the New Hollywood, Blue Velvet remains one of the most integral of American films. Similar to Taxi Driver in that it's the disturbing portrait of the evil that lurks under the veneer of the American Dream, Lynch's masterpiece is a surreal mystery film with some of the greatest performances out there. Dennis Hopper truly disturbs as the unknown-gas-sniffing, sexual deviant and psychotic Frank Booth: one of cinema's greatest villains.

M*A*S*H (Robert Altman, 1970)

A little bit different than the spin-off television series, Altman's film is more biting, satirical and even a little bit bawdy -- but always worth a good belly laugh.

Annie Hall (Woody Allen, 1977)

This Best Picture winner is sometimes maligned by fanboys as the film that beat Star Wars for the Oscar, but it's difficult to argue after having seen it. Hilarious from start to finish, with some miraculous filmmaking skill and wonderful non-sequiters. Diane Keaton justly won the Academy Award for her iconic performance as the titular Annie Hall.

The Last Picture Show (Peter Bogdanovich, 1971)

This stark coming-of-age tale was one of the major breakthroughs of the New Hollywood. A melancholic and moving view of a small mid-west town, with strong performances and homages to Classical Hollywood cinema.

Silent Cinema

While there are many places to begin with an incredible wealth of material, it seems that many audiences either don't know where to begin or are hesitant to start, afraid that they will be bored.

Nosferatu (FW Murnau, 1922, Germany)

This unauthorized version of Dracula was almost completely destroyed by Bram Stoker's widow. Thankfully, she didn't succeed, and we now have the ability to see one of the most entertaining and effective of all silent films. Max Schreck's remarkable performance as the vampire has become the stuff of legend, with fanciful suggestions that he was indeed a vampire himself (the basis of the 2000 film Shadow of the Vampire): how else can you explain those hypnotic, unearthly movements, and that incredible stare and makeup?

Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927, Germany)

More hypnotic movements in this German Expressionist masterpiece and one of the most influential science fiction pieces. The narrative is near-mythic in its battle of good and evil, but it's the massive visuals and the towering art direction that make this a must-see for anyone who considers themselves a lover of cinema.

The Red Spectre (Sigundo de Chomón and Ferdinand Zecca, 1907, Spain)

This is one of my professor Tobias and mine favourite films, and a perfect example of what Tom Gunning calls the Cinema of Attraction. A devil-like figure performs tricks and magic.

Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalì, 1929, France/Spain)

No art house list would be complete without Un Chien Andalou. Just watch it, and don't read anything about it before you do. You'll, uh, thank me.

Three East Asian Films

Late Spring (Yasujiro Ozu, 1949, Japan)

Ozu's meditative style is often called the 'most Japanese' of his peers, with a purposeful but slow pace and muted yet strong emotions. Late Spring may be considered by many as lesser than his masterpiece Tokyo Story, but I find the film to be one of the emotionally powerful films ever made. A widowed father watches as his only daughter goes through the milestone of marriage.

In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar Wai, 2000, Hong Kong)

Contemporary Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar Wai made quite a splash with this film just over a decade ago. It's oozing with passion from every shot, and the romance is humid yet never quite consummated. A beautiful film.

Rashomon (Akira Kurosawa, 1950)

One of my personal favourites, Rashomon is Kurosawa at his most focused and inventive. Multiple people have witnessed a murder, but each have different stories to tell of exactly what happened. Who is telling the truth? Is there any way that we can determine this?

Thursday, March 21, 2013

Quick Reviews

Gentleman's Agreement (Elias Kazan, 1947)

Could be described as one of those "vegetable movies" that are 'good for you', perfectly nutritious and tasty in its own right, but not one that you're too keen on anyways. The story is simple: a journalist pretends to be Jewish for 8 weeks in order to write a story on anti-semitism. Quite the timely film, especially given that the Second World War and the Holocaust were only a few years prior.

The film is marred by a script that simultaneously tries to be serious and casual. The result is a mannered overacting, with the leads of Gregory Peck and Dorothy McGuire having Serious Discussions while romancing, trying to be naturalistic --Kazan's specialty with the Method school of acting, used to glorious effect with Brando a few years later in A Streetcar Named Desire and his other Best Picture winner On the Waterfront, also nabbing him his second Oscar-- but the dialogue is just far too written. No one speaks like this, and when the film is trying so hard to attain a sober realism mixed with a New York looseness... it just doesn't work out as much as the filmmakers are hoping.

Yet the supporting cast is fantastic, with Anne Revere (Mrs. Green), John Garfield (Dave Goldman) and a young Dean Stockwell each giving excellent turns that do manage to be naturalistic and loose. Celeste Holm won the Oscar for her supporting turn as gossip columnist Anne Dettrey, and it's not undeserved: she succeeds with the over-written dialogue, turning it into a wounded urbanite droll with just the right amount of near-screwball bubbliness.

There are some stunning moments in the film that profoundly capture the experience of bigotry: the silence of other guests at a hotel, the heartbreak of a child that has just been called a racial slur, the flippant aggression of a drunken man.

You could say why not just hire a Jewish writer? --but the point is that Green is someone who temporarily shifts his privilege, going from one identity to another despite looking and acting the same. Understandably, this film is used in school curricula, although I suspect the dryness of the film may turn off the students whom could use this message the most.

My favourite exchange, which slyly hints at some other forms of discrimination:

Tommy: "I don't like fruit."

Mrs. Green: "You like bananas."

Tommy: "Well, they're different!"

B+

Grand Hotel (Edmund Goulding, 1932)

Joan Crawford plays a young stenographer with razor-sharp wit and a bit of bubbly girlishness. It's a surprising turn, especially for us who are accustomed to her more serious or campy roles from later in her career. In fact, the grand cast as a whole is just excellent, but the filmmaking craft itself is not to be ignored, either. Brisk editing, interesting stories, and old Hollywood charm with just the right amount of camp from director Goulding.

A

Suspicion (Hitchcock, 1941)

Hitchcock lite, but an interesting turn for the director as it emphasizes the romantic comedy above the suspense. Joan Fontaine earned an Oscar for her performance, which I must admit I don't quite understand. I found her to be a near-parody of the chaste, bookish 'good girl', and lacking the depth that Cary Grant gives to his role. He is fantastic, as usual, in his turn as playboy, charming bastard and possible murderer. Hitchcock seems to be on auto-pilot here, without the sometimes goofy expressionism and flair he gives his other films.

B

The People vs. Larry Flynt (Milos Forman, 1996)

Milos Forman at his most biting, it's a material match made in heaven. Only his early Czech works stand up to it in pure political satire, but this is just another reason why Forman is in my mind one of the premier directors of the second half of the 20th century. We have our fantastic performances: Woody Harrelson is dynamite as the titular loveable slime ball, and Courtney Love is every bit as good in her doppelgänger role. Forman's pacing is swift and furious, with hardly a breath taken between zingers, and the film's loose feel fits perfectly. His ironic use of classical music adds to the delicious veneer of respectable scum, and we genuinely care for these riff-raff of porn pedlars, cheering as they defend their freedom of speech... even if we find them tasteless, vulgar and pretty much some of the most disgusting caricatures of America. Edward Norton shines in a supporting role as Flynt's long-suffering lawyer and fierce advocate.

A+

Tootsie (Sidney Pollock, 1982)

The relationship between men and women in the modern world: it's a theme that's been done a million times, but for whatever reason, 1982 was a year in which Hollywood cinema was bursting at the seams with gender theory. Victor/Victoria, The World According to Garp, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas... and the most popular of them all and second-highest grossing film, Pollock's Tootsie.

Where to begin? The script! Oh, the crackling script. Just some of the gems:

"I never said I love you -- I don't care about you! I read The Second Sex. I read The Cinderella Complex. I'm responsible for my own orgasms. I don't care! I just don't like to be lied to!"

"I was a stand-up tomato: a juicy, sexy, beefsteak tomato! Nobody does vegetables like me. I did an evening of vegetables off-Broadway. I did the best tomato, the best cucumber... I did an endive salad that knocked the critics on their ass!"But the film also features a near movie-killing awful score that sounds like a cheap 70s television drama. A song montage at a farm is simply wretched, yet was inexplicably nominated for Best Original Song at the Oscars (as was the film for Sound, for reasons unknown). Jessica Lange won the Supporting Actress Oscar for her role as Hoffman's love interest, but it's Terri Garr's performance as Sandy is the best of the lot, besides Hoffman's powerhouse role as the gender-bending cross-dressing 'masculine woman' Dorothy Michaels. It's an astonishing turn, and testament to Hoffman's talent.

A-

Sunday, March 3, 2013

Quick Review: "The Boys from Brazil"

The Boys from Brazil (Franklin J. Schaffner, 1978)

Three Academy Award nominations: Best Actor in a Leading Role (Laurence Olivier), Best Film Editing, Best Original Score

A thriller with a tinge of science-fiction, The Boys from Brazil is a rather campy romp, and really only enjoyable when seen through this light.

The acting as a whole is pretty awful, with a plethora of supporting and cameo roles from wooden actors giving just wretched performances. At the centre are acting legends Laurence Olivier and Gregory Peck, who chew through the scenery and are clearly having a good time. It's an infectious attitude, and with a strong supporting turn from another legend James Mason, it's a breezy entertainment.

Olivier managed to nab an Oscar nomination for his role as aging Austrian Nazi-hunter Ezra Lieberman, and it's not entirely without merit. For the first stretch, his character may seem a bit too much with his thick accent and overt mannerisms, but by the end it's a lived-in role. We view Lieberman not as a caricature --which he seems to be at the start-- but instead as a fully fleshed, if eccentric, character. But the star here is Gregory Peck as Dr. Josef Mengele, the infamous Nazi "Angel of Death". As a physician in Auschwitz, Mengele performed many human experiments and murdered thousands of prisoners, his research focussing on heredity, twins and abnormalities. They're a powerful acting duo, and are clearly trying to 'one up' another to see who can have the juicier performance.

Unfortunately, Jeremy Black's performance as the Hitler clones is just about one of the worst performances I've seen from an A-list Hollywood film. "But Andrew, he's just a kid!" Yes, and a kid with zero acting chops. His attempts at a British accent are hilarious.

In his German form, he's a budding Nazi youth with a clarinet, practically screaming at his mother and on the edge of muttering some Ayrian supremacy. But I must admit that he is one creepy looking kid, with that jet black hair and piercing blue eyes.

But the film is primarily a golden artifact of camp. I mean, just take this exchange, which clearly counts as one of the greatest in Peck's career:

Three Academy Award nominations: Best Actor in a Leading Role (Laurence Olivier), Best Film Editing, Best Original Score

A thriller with a tinge of science-fiction, The Boys from Brazil is a rather campy romp, and really only enjoyable when seen through this light.

The acting as a whole is pretty awful, with a plethora of supporting and cameo roles from wooden actors giving just wretched performances. At the centre are acting legends Laurence Olivier and Gregory Peck, who chew through the scenery and are clearly having a good time. It's an infectious attitude, and with a strong supporting turn from another legend James Mason, it's a breezy entertainment.

Olivier managed to nab an Oscar nomination for his role as aging Austrian Nazi-hunter Ezra Lieberman, and it's not entirely without merit. For the first stretch, his character may seem a bit too much with his thick accent and overt mannerisms, but by the end it's a lived-in role. We view Lieberman not as a caricature --which he seems to be at the start-- but instead as a fully fleshed, if eccentric, character. But the star here is Gregory Peck as Dr. Josef Mengele, the infamous Nazi "Angel of Death". As a physician in Auschwitz, Mengele performed many human experiments and murdered thousands of prisoners, his research focussing on heredity, twins and abnormalities. They're a powerful acting duo, and are clearly trying to 'one up' another to see who can have the juicier performance.

Schaffner's film is a bit deranged, which I think is a given considering the material: the clones of Adolph Hitler being born around the world, and now a plan to murder the adoptive fathers. Why? To mirror the adolescence of Hitler himself, whose father died at 65, and ensure similar environmental conditions.

I see...

Of course, it's a ludicrous plan, as much as they try to make it seem legitimate with a scientist explaining (pretty accurately) the process of cloning.

Science!

But of course, the flaw is in the environmental conditioning: the good old argument of nature vs. nurture. This, of course, is why Mengele goes with 94 clones instead of just a few: quantity. Sure, it may ignore the political, ideological and economic conditions of Hitler's childhood, but at least one will turn out the same, right?

Unfortunately, Jeremy Black's performance as the Hitler clones is just about one of the worst performances I've seen from an A-list Hollywood film. "But Andrew, he's just a kid!" Yes, and a kid with zero acting chops. His attempts at a British accent are hilarious.

"Dohn't you understAAAhnd, you AHHHHss?"

In his German form, he's a budding Nazi youth with a clarinet, practically screaming at his mother and on the edge of muttering some Ayrian supremacy. But I must admit that he is one creepy looking kid, with that jet black hair and piercing blue eyes.

I mean, just look at the bastard.

James Mason is a lone bastion of restraint in the bunch, which is remarkable considering his character: a suave, urbane and even effeminate Nazi. I've always though that Mason is one of the greatest actors of his generation, and if he can manage to bring some hint of depth and even subtlety to something like The Boys from Brazil? Well, kudos to you, good sir.

Easily his most fabulous role, darling.

But the film is primarily a golden artifact of camp. I mean, just take this exchange, which clearly counts as one of the greatest in Peck's career:

"Shut up, you ugly bitch."

Or this insert, with a Hitler clone cackling wildly as his mother discovers two dead bodies upstairs:

"NAAAAANCY! NAAAAANCY! HAHAHAHAHA"

And seriously, who takes the time to write the name of your archenemy on the board, menacingly askew?

So it's certainly an entertaining flick, with a trio of great actors giving flashy performances and a pretty bonkers narrative. But it doesn't help Schaffner's reputation in my eyes, whom I've found to be a pretty mediocre director. Patton was helped by Scott's legendary performance and a decent script by Coppola, but otherwise, I'm not finding much to praise.

What else? Jerry Goldsmith's score seems to be in on the campiness, with its main waltz motif almost sarcastic in its playfulness. The editing is remarkably clunky, surprising given Robert Swink's pretty fantastic filmography. Steve Guttenberg (whom you may remember from Three Men and a Baby) is simply wretched in his (thankfully) brief performance as a rookie Nazi hunter who uncovers the big plan.

B+

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)